Different kinds of time

If you work full time, in Sweden, you spend about 2 000 hours per year doing your job. That’s a lot of hours, but depending on how you spend those hours the outcome will differ a lot.

I think a lot about time and in this post I want to introduce you to a concept I picked up when I started to study at university: Unintentional Time.

Dead Time

But before we talk about unintentional time we need to talk about its sibling: dead time.

If you work in IT you come across “dead time” every day.

It is the 15-minute-gap between one meeting that should’ve ended 10:00 and the 10:30 one.

It is the time between git push and you getting a result back from your pipeline.

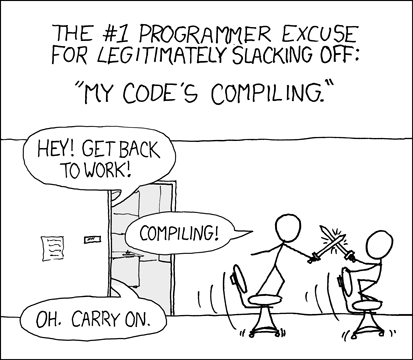

It is the time you wait for your code to compile.

Periods of dead time are usually short and you cannot really do anything meaningful with that time anyway. We accept that it exists and move on.

Unintentional Time

If dead time is: useless time that cannot really be used for anything, we need another word for: the time you planned to use for implementing a new feature but instead spent discussing a problem with someone who popped over to your desk only to realize that the problem is multifaceted, complex and require that you set aside a big chunk of time to look into it more thoroughly.

It’s the time when you search for datetime to string with timezone for the 43rd time and find yourself (25 minutes

later) reading about why New Zeeland’s clock is currently UTC+131.

Or the 45 minute lunch that turned into 70 minutes, because you had such a good time.

Or when you grab a colleague and say: “Let’s go into this room and use the whiteboard to brainstorm a bit.”

This time is not useless (which is good), but it’s unintentional (which is really bad).

Why is unintentional time bad?

When I went to music school, I was taught the importance of practising with intention. It was not enough to “just play or sing”, I had to plan what I was going to do and then execute with focus and intentionality. Failing to do so would not be a total waste of time, but it was evident that the intentional practice sessions yielded far better results than their unintentional counterparts.

It’s the exact same thing with the 2 000 hours per year you spend doing your job. In order to get the most out of those hours, you need to plan what to do with them and then perform your plan with deliberation.

Now, someone might say: “Who cares?”, and I guess that’s fine.

To each their own.

But few things frustrates me like wasting time. Because wasted work time turns into wasted free time; and I value my free time very, very, highly.

Because when push comes to shove, I don’t work 2 000 hours per year because I love what I do. I work because I need money and because I want to occupy myself with something interesting. I think trading my skills for cash satisfy those criteria and I want the time traded to be as meaningful to me – and as valuable to the company paying me – as possible.

Do the same thing, with intention

Because I value my time so highly, I try my best to always spend my time with intention. When I decide to do something, I do that thing. Then I do the next thing. And the next thing.

And just to be clear. I love deep diving into niche problems and 70 minute lunches, but I want to plan for them. I want them to be intentional.

Do you want more?

A couple of years ago I heard CGP Grey talk about unintentional time in Cortex: Productivity 101. It’s worth a listen and the link takes you straight to their time-tracking discussion.

Furthermore, one reason I really like remote work is because of the opportunities it brings with respect to spending my time with intention. I have started a post about this too and hopefully it will be published soon.

-

It’s because of DST. ↩