Automate everything and document why

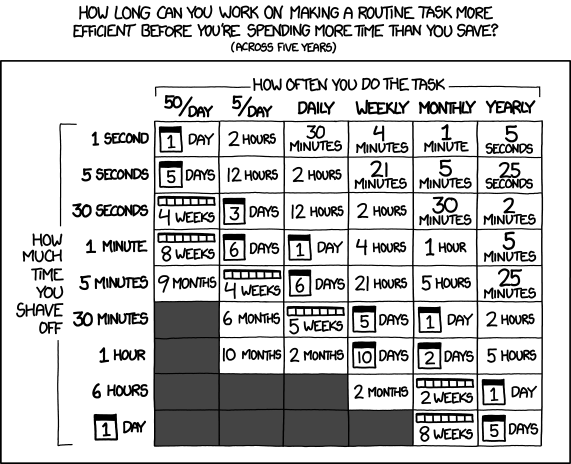

Almost 2 000 comics (and over 12 years) ago1, Randall Munroe created the XKCD Comic Is it worth the time? (seen below).

I have carried this table in my mental hip pocket, always ready to show a doubting customer or team member how much time we can save if we automate a specific task.2 However automation is not solely about saving time. I would even argue that the time saved by running an automation, instead of doing the automated tasks manually, is just a positive side effect of the automation.

The primary reason to automate something is not to save time, it is to codify knowledge and ensure reproducibility.

As an example, the table tells us the following:

- Frequency of task: Monthly

- Time shaved off task: 5 minutes

- Total time saved over 5 years: 5 hours

One could look at this and think: “As long as we believe we will do this task for the next five years and we spend less than five hours automating the task, it is worth doing.”, but I think that mindset is wrong. There is more to be gained! By automating a task, we create a step-by-step guide which tells a computer (and therefore us and our future colleagues) exactly how to perform the task. The code we write is unambiguous3, whereas most documentation I have read (and written) is not. In order for our automation to be useful, it must omit nothing; but authors of documentation frequently forget things or simply ignore to add steps they consider trivial.

Another important thing about the automation is that it – if written properly and executed regularly – will break and alert us that something about our target system has changed. Even the most well written runbook can become outdated and my experience is that ensuring all of our documentation in Confluence is still up to date and accurate, is an infrequent issue in most teams’ sprints.

The code is the documentation

I have always been a proponent of documentation. Having worked as a consultant the majority of my career, few things make me happier than a well functioning internal wiki, to kick start an assignment and getting up to speed. I am also really fond of writing documentation; leave me alone with draw.io and a markdown editor and I’ll be in my happy-place. Over time though, I have steered away from writing pure documentation (i.e., a separate text file describing a resource or process) and instead focused on trying to always incorporate the “documentation” into the resource itself.

In the light of the introduction of this post, I think the reason is obvious. If given the option, I will always choose to codify my knowledge in an executable format; because the code is truth.

I’m sure you have heard the phrase:

The code is the documentation.

You probably have an opinion about the phrase too.

I think there are developers who throw this phrase around simply because they dislike writing documentation, both as comments in their code but also as standalone documents. Maybe it’s out of laziness, incompetence, or they see the reasoning I lay out in this post and believe it’s reasonable to take it to its utmost extreme. I do not believe this extreme is reasonable. Most of the time, we shall not write code, leave it without comments, and expect our future selves and colleagues to understand it. At least not benefit from it fully.

However, I also think there are developers out there who has internalised the same conclusion as I have: It is very difficult (maybe even impossible) to write documentation that describes anything in a more exact and concise way than the source code itself already does. Therefore, any documentation we write must be well thought through, kept up to date, and describe why we chose to write a particular piece of code. There’s almost never any reason to describe what the code does.

What, when and how I document

To wrap up this post, I want to give a short list of kinds of documentation and how I use them.

Runbooks

The only time you should write a runbook is as a notes-document, the first time you step through a procedure. That way, when you automate the task you can reference your runbook before you delete it.

Naturally, only Sith deal in absolutes.

Way of Working documents

Early in my career I held a lot of scrum master/team lead positions. I also (therefore?) wrote a lot of documentation about different processes. My closest manager(s) did and the product owners usually did too. They usually loved them. Likely because they did not talk to the team every day, the documents became the window through which they tried to understand why the teams made certain decisions and worked in certain ways. PO:s in particular also loved to use the way-of-working documents in their argumentation when there was a disagreement.

Adherence to those documents from the team? Let’s just say it was not 100%.

What I have come to learn is that it’s futile to attempt to change ways of working by defining processes. Writing down the current ways of working is also just busy work, because it is close to impossible to describe all intricacies that goes on in a team on the daily. Should you succeed, the document is just a snapshot and ways of working are dynamic. It is bound to become outdated.

Source code

If your code achieves what it is meant to do, you should – within reason – not have to document what it does. However, it is certainly a good idea to spend quite a lot of time writing your code in a way that is understandable.

Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.

– Harold Abelson (Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs)

Once I have unlocked the “understandable and functional-code” achievement, I usually spend some extra time going over the code to see if it’s clear why I wrote the code in this way. I tend to err on the side of caution and comment a little bit more than what is necessary, but I think this is reasonable approach.

Architectural Decision Records (ADR:s)

Sometimes a team or organisation makes a decision that is worth remembering. Well, not only the decision itself, but the rationale behind the decision and also the consequences of making the decision. Adding a comment to a source code file is a bad idea, because it would probably result in a comment longer than the combined code in that file but also because it hides the decision in a stowed away file in a specific project.

The concept of Architectural Decision Records is a great way to document such decisions. I usually propose that ADR:s contain the following four headings:

Context

Decision

Rationale

Consequence

A pleasant side effect of this practice is that your aggregated ADR:s is likely to inform your team’s and/or organisation’s ways of working. For instance, in my current assignment, we write specific Team ADR:s to document decisions we have made about concepts, tools, or best practices. We keep these ADR:s in a dedicated repository and frequently reference them. When an ADR becomes outdated we update it and make it clear it is no longer to be adhered to, but we leave it in the repo and if there’s a new ADR replacing the old one we reference the new one.

Git

My opinion is that developers are usually not great at neither writing nor reading commit messages. If we utilise our

commit messages to convey meaningful information about our commits – as opposed to just writing fix and add feature

x – we can really help our future selves and our colleagues.

As I wrote earlier, if we write understandable source code and include comments that explains the context for particularly intricate pieces of code, that is good. We can improve on this further by adding more prose like explanations and motivations in the commit message.

I am a fan of Conventional Commits.

-

At the time of committing this, the latest XKCD is number 3116: Echo Chamber. ↩

-

The comic does not actually say that automation is the goal, but as someone who spends most of their work days automating things, this is where I was taken by the comic. ↩

-

I’m sure you can come up with an example where this is not true, but that’s beside my point. ↩